If you’ve spent time practicing with me, you know that I like to organize postures into categories. Sorry, I’m a Virgo. I’m also from the Midwest which is why I’m apologizing for something I don’t need to apologize for. In my defense, Patanjali was an organizer and list maker. So was the Buddha. I’m in good company.

Naturajasana falls into the backbending category in which the arms are reaching overhead and holding the foot/feet. Notable members of this family include the One-Legged King of Pigeon postures (Eka Pada Rajakapotasana postures), the ridiculously difficult arm balance named Kapinjalasana, and Hand-to-Foot Boat Pose (Padangusthasana Dhanurasana). So, yeah, this pose group is difficult.

Writing as someone with a mortal’s body who can’t directly hold my foot in ANY of these postures, I am thankful that they’re all highly accessible with a strap. In fact, these are my favorite backbends to practice, and I’m convinced that I feel every bit as good in these postures as someone who can hold their foot without a strap (or, at least, that’s what I tell myself while I cry myself to sleep).

See also Backbends: When and Why to Engage Your Glutes

One Thing to Know About Natarajasana

This entire family is challenging, but Natarajasana’s difficultly stands out. In fact, a highly skilled and capable student in my recent workshop in Copenhagen asked me why she wasn’t able to do Natarajasana, even though she had deep backbends. This is how the conversation went (with a few embellishments here for your entertainment):

Student: Why can’t I hold my foot in Natarajasana, when I can hold my foot in similar postures like Pigeon Pose?

Me: You’re not spirituality pure enough and the only way to burn the necessary samskaras is to provide your teacher with significant cash donations.

Student: No.

Me: OK. There’s another reason, and it’s simple. If you have the flexibility to hold your foot in Pigeon Pose, you probably have the flexibility to hold your foot in Natarajasana. The challenge is that it’s much more difficult to access your flexibility in Natarajasana than Pigeon.

Student: OK.

Me: Let’s quickly break this down. In Pigeon Pose, you have a lot of contact with the floor. Your front shin, your front knee, your front hip, and your back knee are in contact with the ground (or props). This means you’re stable and you have good leverage. When you’re stable and you have good leverage, you can generate more motion in your body to do your backbend. Plus, in Pigeon Pose, your center of gravity is close to the floor.

Therefore, in Pigeon Pose you have: More stability + more leverage + lower center of gravity = more range of motion.

Compare this to Natarajasana. In Natarajasana, your entire base consists of your standing foot. That’s all. In addition, you’re standing upright so your center of gravity is much higher. Pigeon is short and squat, Natarajasana is long and narrow.. This means that you have much less stability in Natarajasana than you do in Pigeon Pose.

When you have less stability, your body creates greater tension to stabilize your shape. This leads to less mobility—or, more accurately, less access to your mobility. You’re still just as flexible, but you can’t access it under the current conditions.

Get the difference? Yes? Good, come to my yoga teacher trainings. No? Good, come to one of my teacher trainings. Sorry, for the shameless plug, but if you’ve made it this far in this tedious article, we share common ground.

Therefore, in Natarajasana you have: Less stability + less leverage + higher center of gravity = less range of motion.

Student: You’re still not getting a cash donation.

That’s how the story goes.

To prove that she was able to do Natarajasana, I supported her raised knee properly and she easily reached back and took hold of her foot. When I provided her with additional base and stability, she was able to access her flexibility—just like she does in the other postures in this family.

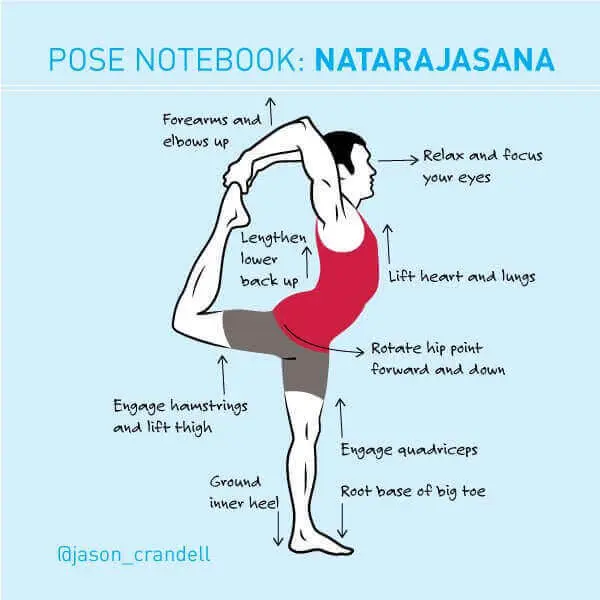

When you don’t have a friend or a teacher to help create stability for you, you can do so by rooting through the base of the big toe, grounding the inner heel, and engaging quadriceps. You could also stand parallel to a wall (on the standing leg side) and place you hand against the wall so that you can feel the activation in your standing leg.

What’s the simple take-away that goes beyond Natarajasana? Sadly, you don’t need to give your teachers cash donations to do more difficult postures. Instead, you have to focus on producing greater stability and activity in your base, so your body is able to move more freely.

{illustration by MCKIBILLO}