QUESTION:

Some teachers tell students not to “squeeze” or “grip” their gluteal muscles (or glutes) in backbends because this will compress the sacrum and lower back. Others say that it’s essential to use the glutes in backbends. What do you recommend?

ANSWER:

First, let’s acknowledge that different students may benefit from slightly different actions in any given posture. So, the most accurate way to answer this question is to say that most students will benefit from engaging their glutes in backbends. Here’s why:

GLUTES IN BACKBENDS: THE ESSENTIAL ANATOMY

The gluteal family is composed of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus. When teachers talk about engaging the glutes in backbends, they’re referring to the gluteus maximus. When we engage the gluteus maximus—particularly the lower fibers near the hamstring insertion—these muscles extend the hip-joint. This is a good thing because we want the hips to extend slightly when we do backbends in order to help decompress the lumbar spine. Gluteal engagement also helps stabilize the sacroiliac joint—which is valuable because so many long-time yogis have hypermobile and unstable SI joints.

But, let’s answer the question with a little more nuance since some backbends are enhanced by gluteal engagement and others are not. Prone backbends like Locust and Cobra Pose probably don’t benefit as much from gluteal contraction because the weight of the pelvis rests on the floor during these postures. This means that you don’t need gluteal strength to lift the pelvis because it stays on the ground in the pose; you also don’t need the stabilization that the glutes provide because the pelvis is supported by the floor.

In kneeling backbends like Camel Pose and supine backbends like Bridge Pose and Upward Facing Bow Pose, gluteal engagement is more helpful. These postures produce a greater degree of spinal extension so it’s even more important that the pelvis and spine move cohesively. Engaging the glutes near the hamstring insertion, will help maintain this balance by rotating the pelvis slightly back over the top of the legs. This will help reduce lumbar compression—the feeling of your lower-back “crunching.” Even more, the glutes help lift the weight of the pelvis in supine backbends. If you don’t use the glutes in these postures, you might unnecessarily burden less efficient muscle groups.

Some teachers and students are concerned that using the glutes will make the knees splay too far apart. This is a legitimate concern, but it’s easily managed. All you have to do in this situation is co-contract the muscles that line the inside of your thighs, the adductors. Firing the adductors while you engage your glutes will keep your thighs nice and neutral.

THE SEQUENCE

In the poses that follow, the prone (face-down) backbends are instructed with passive glutes, whereas the kneeling and reclined backbends are instructed with active glutes. I encourage you to experiment in these postures and observe what works best for your body.

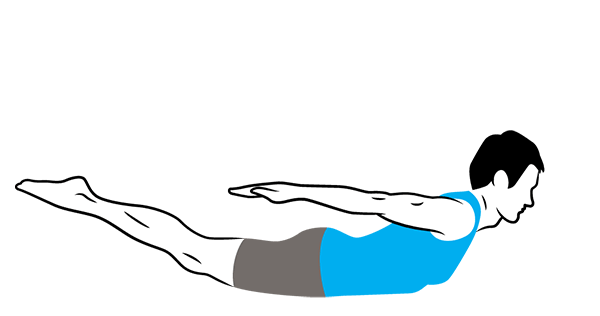

Locust Pose

Lie down on your belly. As you exhale, lift your upper-body away from the floor. Root down through the top of your feet and ground the top of your smallest toe. Keep the glutes passive and focus on the work of your spinal muscles.

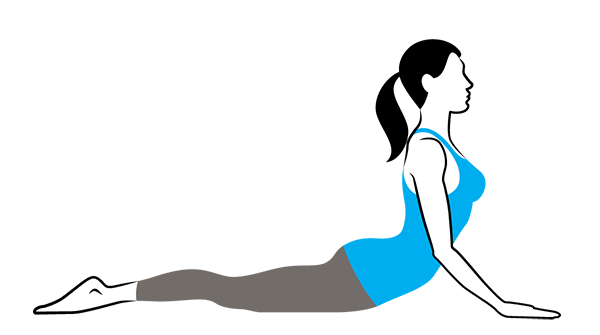

Cobra Pose

Again, start on your belly. Place your hands on the floor on either side of chest. Press down through the tops of your feet and your pubic bone as you partially straighten your arms. Draw your shoulder blades down your back and hug your elbows toward your sides. Keep your glutes passive and allow your spinal muscles and arms to guide you into the posture.

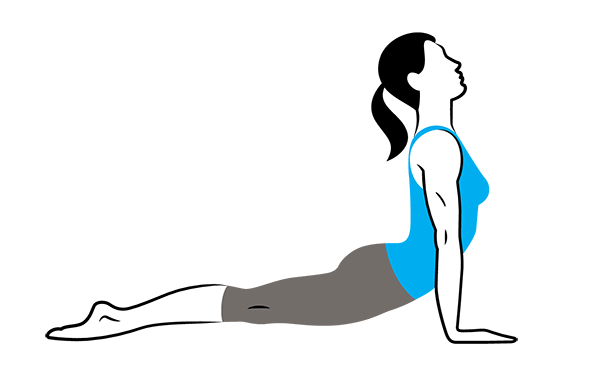

Upward-Facing Dog Pose

Come into Upward-Facing Dog from Chaturanga. Once you’re in Updog, allow the glutes to be relatively passive. Focus on grounding down through your fingers, hands, and feet while lifting your thighs, hip-points, and chest.

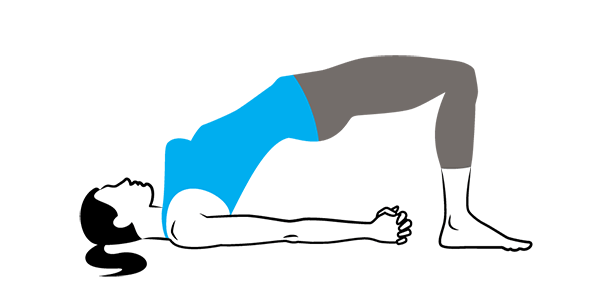

Bridge Pose

Lie on your back, bend knees and place your feet flat on the floor, close to your hips. Separate your feet hip-width. You can either keep your arms by your sides or clasp your hands underneath your buttocks. Press down through your feet and raise your hips. Your glutes will fire to help raise your hips. Gently engage your inner legs by imagining that you’re squeezing a block between your thighs.

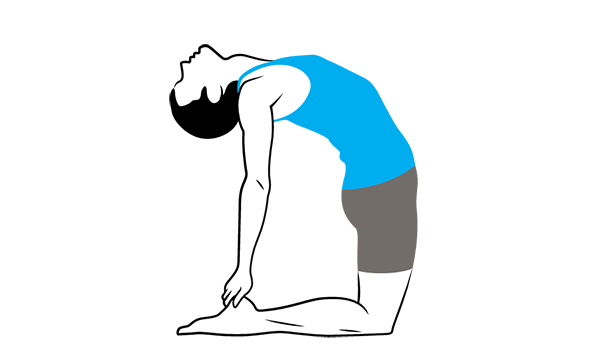

Camel Pose

Kneel on your mat and touch your hip-points with your finger tips. If you have a block, place it between your inner thighs. Lift your hip points up and lengthen your tailbone down. This action will begin to fire your glutes near the insertion of the hamstrings. (One of my teachers, Richard Rosen, calls this part of the glutes the LBMs, or lower buttocks muscles.)

Take your hands to your heels, lift your chest, and lengthen your breath. If there’s a block between your thighs, squeeze it firmly. This engages your adductors and keeps your thighs parallel to each other.

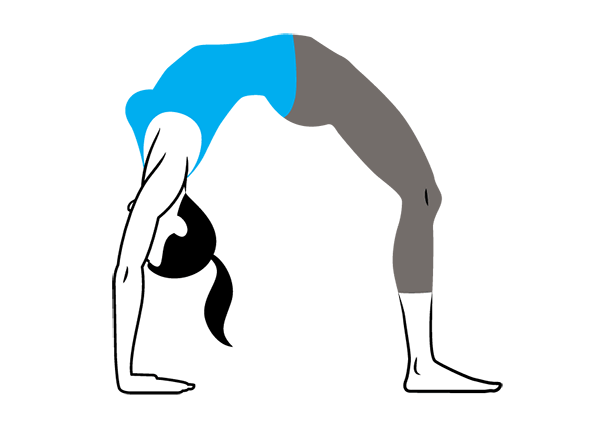

Upward Bow Pose

Lie on your back like you did for Bridge Pose. Separate your feet hip-width. Lift into the posture on your exhalation. Once you are in the posture, bring your awareness to your glutes. Given the demand of the posture, your glutes will be firing. Feel the support that they’re providing while being mindful to simultaneously engage your inner thighs by hugging them toward your midline.

{illustrations by MCKIBILLO}